Hoffnungstal, Bessarabia – History of a German Village (Part 5)

This is part 5 of 6 blog posts on my grandfather’s home village of Hoffnungstal, Bessarabia (now Ukraine).

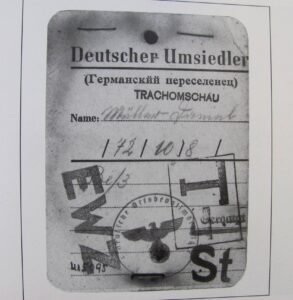

Identification card for those being resettled (Source: Hoffnungstal: Bilder einer deutschen Siedlung in Bessarabien, from the collection of Erhard Mueller)

The beginning of the end … leaving Bessarabia

The year 1940 was a major turning point in the history and life of the Bessarabian villages, including Hoffnungstal. As part of the Versailles Treaty after WWI, Bessarabia had been annexed to Romania in 1918. In June 1940, Soviet troops demanded the Romanian evacuation of Bessarabia. As part of the Molotov-Ribbentrop agreement, the German colonists would be resettled to Germany as the Soviet Union claimed the land of Bessarabia.

Although the villagers could not know what would lie ahead for them, it was immediately clear that their position had changed. All schools were closed and hospitals were seized by the Soviet authorities. Traffic was restricted on the roads and all private travel by train was forbidden.

Taxes for 1940 had to be paid again in full, even if they had previously been partly (or even fully) paid. Overnight, the Romanian lei was declared to be invalid currency, meanting the taxes had to be paid in material goods (grain, etc.) An arbitrarily determined amount from the 1940 harvest had to be handed over to Soviet authorities. Often there was alleged contamination of the grain, and the villagers were forced to hand over additional amounts above and beyond what would pay their debt.

Soviet authorities nationalized many businesses including banks, companies with more than 20 workers, book and printing shops, electric facilities, and schnapps and wine distilleries. In addition, they took over all the schools, hospitals, drugstores, movie theaters, museums, and hotels throughout Bessarabia. The German villagers faced all of this with resignation, saving all they could of the possessions that they still had.

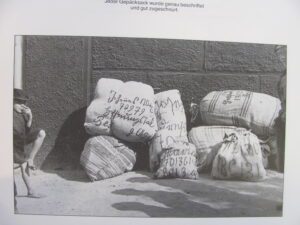

Packing up household goods for the journey to Germany (Source: Bilder einer deutschen Siedlung in Bessarabien, from the collection of Erhard Mueller)

The Umseidlung (Resettlement)

On September 15, 1940, the German Resettlement Commission arrived in Hoffnungstal to begin assessing the villages in the area for resettlement. The assessment continued until about the end of October. The Commission went door to door through the village, assessing the contents and property of each family. The villagers would only be allowed to take a small number of possessions with them—the rest they were to leave to the Russians and they were to be reimbursed when they had returned to Germany.

Women, children, and the elderly would travel by truck. The men would travel with the horses and wagons. Those traveling by truck could take only carry-on personal items. Those traveling by wagon could take one wagonload of possessions per family. Officially, each family was allowed to take some livestock, limited to two horses or oxen, one cow, one pig, five sheep or goats, and some poultry. In reality, however, the villagers were not allowed to take livestock with them due to “transportation” problems. The cherished Bessarabian horses were sold or later requisitioned for a German cavalry unit.

The villagers were allowed to take only 2,000 lei (probably about $3 U.S.) per person, plus the proceeds of any documented sales of personal property. No gold or silver in ingot or dust could be taken. Gold or silver in watch chains, wedding bands, etc. was limited to 500 grams per adult.

Weapons, binoculars, or any items of military origin were forbidden (except for one gun per hunter). Manufactured items or store-bought clothing were limited. Family photos could be taken along, but no other photos, documents, or printed items could be taken. No engine or electrical-powered devices could be taken, nor any seeds, seedlings, or grape vine cuttings.

The farewell service in the Hoffnungstal cemetery (Source: Hoffnungstal: Bilder einer deutschen Siedlung in Bessarabien, from the collection of Erhard Mueller)

On September 26, a farewell service was held in the Hoffnungstal cemetery, and on October 1, the families of Hoffnungstal began leaving their home of almost a century. First the women, children, and the elderly from Hoffnungstal’s east street left.

They went by truck to the Danube harbor at Reni, then by ship to Semlin near Belgrade. After spending two days in a refugee camp at Semlin, they went by train through Vienna to the Sachsen area of Germany to a refugee camp near Chemnitz.

The men from Hoffnungstal’s east street left on October 2 by horse and wagon. At the border between Bessarabia (now Russian-occupied) and Romania, all the wagons had to be unloaded for a customs spot check. All bags, pillows, etc. were opened and checked. Then everything had to be packed up again and loaded back on the wagons. They crossed the river on a shaky bridge, headed for the harbor at Galatz.

At Galatz, the luggage was unloaded and stored. (The Hoffnungstalers would not see these possessions again for two years.) Wagons and horses were handed over to the German military to be used as a cavalry unit in the Balkan campaign. The men, along with their carry-on personal possessions, took a ship up the Danube to rejoin their families at the camp near Semlin, then later to the refugee camp near Chemnitz.

Wagons leaving Hoffnungstal (Source: Hoffnungstal: Bilder einer deutschen Siedlung in Bessarabien, from the collection of Erhard Mueller)

The Hoffnungstalers living on the west street followed the same journey about a week later, with the women and children leaving on October 9, and the men leaving on October 15. They also ended up in the refugee camps near Chemnitz.

About 50 people from Hoffnungstal had been too sick to travel by regular truck—these people were transported by ambulance or special trucks to Semlin along with sick people from other Bessarabian villages. In many cases, their families, waiting for them in Chemnitz, never saw them again.

Living as refugees in Germany

Mealtime at a refugee camp in Germany (Source: Hoffnungstal: Bilder einer deutschen Siedlung in Bessarabien)

The camps at Chemnitz were gymnasiums, factory halls, restaurants converted for the purpose of housing refugees where everyone slept together in big rooms with many cots. Many of the young men were drafted into the German army, the Wehrmacht. Other men were assigned to work in the factories—difficult physically as they performed hard labor on meager rations, and difficult emotionally for those used to being outdoors working their own fields or working as independent craftsmen.

Prior to resettlement, each person had to pass the “citizen harmonization” process. This testing consisted first of a physical examination, and then a race-political examination given by the Nazi Immigration Office and the National Security Service. This involved proving their German ethnicity so they could be declared “racially useful and politically dependable.”

(To be continued)

By 1940, most of me immediate family had already left Bessarabia (1902), but there were many extended family members in the villages. Some of them probably never got to leave. Am I correct to believe that the Russians and total disregard for the cemeteries? About 10 yrs ago some family went back to look for headstones. A few were found, but they were toppled over in a cow pasture. So sad.

Hi Marilyn,

In Besssarabia, nearly all the Germans left in 1940. There was a VERY small minority that stayed (usually because of a marriage with a local family or something like that). Now for the Germans living east of the Dniestr River (in the Odessa region, Mykolaiv, etc.), it’s a very different story. They went thru hell between 1917 and 1940 under the Soviet regime. Many starved alongside the local Ukrainians (the Holodomor), many were executed, many were deported to Siberia or other places east. Many of them never got out.

As for the cemeteries, from my travels there, I would say most of the German cemeteries are gone, though a few remain – Teplitz, Tarutino are a couple that I saw.

And although I wish the German cemeteries had remained intact, I have some sympathy for the local people (whether they were ethnically Ukrainian or Russian). The Nazis swept through that area during WWII and killed many locals. After they left, the locals were understandably angry at anything German, even our ancestors’ cemeteries and even though most of our ancestors had nothing to do with the Nazis.

Also, I remember talking to a Ukrainian woman in an Odessa-area village (Neuberg, I think). She was tending graves in the Ukrainian part of the cemetery and we asked her about the German graves. She said, “All you Germans come and ask why we’re not taking care of the German graves. We don’t even have money to take care of our own graves. How do you expect us to do take care of yours, too?”

I thought she made a good point.

My sister and I traveled to Ukraine in 2003. Our Grandfather, his wife and 2 sons fled from Russia in 1923. Grandfather was 60 years old but had to leave his life’s work behind.

We did find the grave stone of the real Grandmother and another grave marker(name plate had been removed) on the farm. The elderly lady that knew were the farm was told us that after WW II the government came with bull dozers and removed all evidence of German buildings.

We have photos of good buildings. You would think that someone would have been useful when there was such a need.

Hi Carl,

In many of the old German villages, the old German houses are still being used today. Very sturdy!

The story about the bulldozers coming, was that in Hoffnungstal? When I was there in 2001, I was told that a Russian military base on the overlooking hill used the houses in Hoffnungstal for target practice, and that’s why they were all destroyed. And walking around, we did find one shell on the ground that would seem to back that up. But you never know. So I’m curious to hear more about the story you were told.

Hello Carolyn,

I came to your site on the Internet research.

My parents, Emil and Klara Müller born Bast both come from Besserabia. My father’s father was named Daniel Müller and lived in Hoffnungstal. My mother Klara Müller was from Friedental. I was very surprised when I saw the pictures on your website (report).

I have these pictures as original in my documents.

– The illustrated ID card (German resettlers front and back)

– The picture with the sacks.

– Farewell Fiedhof

– The image of the car collon

Can you write me where you got the pictures?

I know that my father has also provided these pictures to the Heimatmuseum in Stuttgart (Germany).

On the occasion of my cousin’s 70th birthday, we have a Bessarabien family reunion next Sunday.

How small is the world!

Greetings from Germany

Erhard Müller

[…] theirs were turned upside down in June 1940 when they learned the Soviets were re-taking the area. The German villagers would have to leave their family homes of more than a century and would be resettled by the Nazis to farms in […]