It Is Not Open to Tourists

When I planned my trip to Krakow in 2006, I had no plans to visit nearby Auschwitz. I was told I’d regret it; that the visit would be memorable. I’ve read a whole booklist of Holocaust books (probably my ethnic German background trying to come to terms with the Nazi German regime) and even visited one (slightly less infamous) concentration camp, Dachau. That was memorable enough.

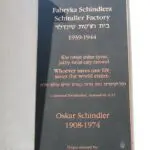

But one obscure entry in my guidebook did catch my eye—Oskar Schindler’s factory. He’d used this factory to convince SS officials that the Jewish prisoners working there were critical to the Nazi war effort. That saved them from being sent to Auschwitz to be killed.

But one obscure entry in my guidebook did catch my eye—Oskar Schindler’s factory. He’d used this factory to convince SS officials that the Jewish prisoners working there were critical to the Nazi war effort. That saved them from being sent to Auschwitz to be killed.

The guidebook warned there was little to see; it was just an empty building slated to become a museum someday. There was certainly little to see on the walk from the tram, just an underpass littered with trash. The factory building itself appeared deserted, the dark windows staring out over the street with a hollow empty look.

There were a couple of people milling around, tourists like me, taking photos. As I snapped a photo of the plaque commemorating Schindler, a man came out of an archway of the building.

There were a couple of people milling around, tourists like me, taking photos. As I snapped a photo of the plaque commemorating Schindler, a man came out of an archway of the building.

“Would you like to see inside?” he asked me and another American woman snapping photos alongside me.

“Uh…”

“It is not open to tourists, but if you want, I can let you in.”

She and I looked at each other. There seemed to be safety in numbers if there was something illicit about this. And we did want to see inside.

“Sure,” we said after a long pause. We stayed together, following him under the archway, then through the door he opened into a small entryway. Apparently the building was “not open” to a great many tourists that day, because ahead of us another group was climbing the stairs beyond the entry.

“This building is not open to tourists, but it was the main office building of Schindler’s factory. Those buildings there,” as he pointed through a window, “are some of the original buildings that existed in Schindler’s time. These,” and he pointed in the opposite direction, “are newer.”

“This building is not open to tourists, but it was the main office building of Schindler’s factory. Those buildings there,” as he pointed through a window, “are some of the original buildings that existed in Schindler’s time. These,” and he pointed in the opposite direction, “are newer.”

“This is not open to tourists, but there is the staircase up to Schindler’s office. Did you see the movie? They used this staircase in the movie. At the top of the stairs is Schindler’s office. Of course, this is not open to tourists, but there is a small film you can see.” He gestured us toward the stairway then slipped back outside, presumably to round up more tourists. I could sense the demand for a donation coming.

Since I vaguely remembered a scene from the movie centered on the staircase, I dutifully took a photo before climbing it to see Schindler’s awkwardly-shaped office with a few random pieces of furniture. A small window looked out over the factory buildings below, the same view Schindler would have seen daily. I couldn’t remember which were the original buildings and which were newer, but it hardly mattered. These rundown buildings had been a place of refuge and hope for 1,100 people who wouldn’t have survived otherwise.

Since I vaguely remembered a scene from the movie centered on the staircase, I dutifully took a photo before climbing it to see Schindler’s awkwardly-shaped office with a few random pieces of furniture. A small window looked out over the factory buildings below, the same view Schindler would have seen daily. I couldn’t remember which were the original buildings and which were newer, but it hardly mattered. These rundown buildings had been a place of refuge and hope for 1,100 people who wouldn’t have survived otherwise.

After watching the WWII film clips playing on the stairway landing, I headed toward the door, pulling out my wallet, expecting to get hit up for a donation by the doorman who’d let me in. But he wasn’t there. No one was in sight as I exited into the courtyard under the archway. I put my wallet away, disappointed I couldn’t somehow express my appreciation for being able to go inside.

Seeing this desolate building without anything resembling a real museum exhibit had been more meaningful to me than a day at Auschwitz. Rather than surrounding myself with the horror of Nazi atrocities, I’d stood in the place where one man—despite being a Nazi party member and war profiteer, despite the risk to himself—had stood up against the evil and darkness around him and had been a source of light. When I think back on my visit to Krakow, I’ll always remember visiting the place where 1,100 lives were saved.

Seeing this desolate building without anything resembling a real museum exhibit had been more meaningful to me than a day at Auschwitz. Rather than surrounding myself with the horror of Nazi atrocities, I’d stood in the place where one man—despite being a Nazi party member and war profiteer, despite the risk to himself—had stood up against the evil and darkness around him and had been a source of light. When I think back on my visit to Krakow, I’ll always remember visiting the place where 1,100 lives were saved.

(Carolyn’s note: Although this building was empty when I visited in 2006, in less than 2 weeks on June 10, 2010, the Historical Museum of Krakow will be opening the Schindler factory as a museum focused on the Nazi occupation of Krakow.)

Carolyn: Great website!! Your name comes up over and over during my research. My mother (93) is from Leipzig. Born a Neumann, married a Lieske. Son Egon. Widowed. To Poland. Then to Siberia (45-55). There she met my dad, a Mennonite from the Ukraine. To Germany in 55. To Canada in l961. I have heard about the war EVERY day of my life. Siberia. Bessarabia. I know All the stories. Or thought I did, until we sold my parents home last spring and I found my mothers ” Aussiedlerpass” from Bessarabia. It blew me away. I had never seen it, although i had heard much about the deportation over the years. Now that my parents are both unable to answer the many more questions that I seem to have, I am saddened that I did not ask them more before. I plan to go to Leipzig in 2015 with the German Verein as they celebrate the 200th anniversary there. My first cousins are all in Germany, Begium, and Siberia. Keep up the great work. I will continue researching your stuff. Louise Wiens (Canada)

Hi Louise, Thanks for your nice words! I haven’t blogged for awhile…need to get back into it!

My Billigmeier family was also from Leipzig, but they left in the 1890s. I’m actually planning a trip there next summer with my cousins.

Let me know if you need any suggestions on your research.