Osthofen, Germany: My Ancestral Town

The town of Osthofen, Germany, was the home of the Schott family from at least1717 to 1809. It is over 1,200 years old, and was first mentioned in 784 in the Lorscher Codex (a manuscript from the Lorsch Monastery). In 784 it was referred to as Ostova. Later names included Osthoven (1262), Osthouen (1268), Ostown (1283), Osthoen (1330), Osthoben (1346), Osthoffen (1438), and finally Osthofen.

The town of Osthofen, Germany, was the home of the Schott family from at least1717 to 1809. It is over 1,200 years old, and was first mentioned in 784 in the Lorscher Codex (a manuscript from the Lorsch Monastery). In 784 it was referred to as Ostova. Later names included Osthoven (1262), Osthouen (1268), Ostown (1283), Osthoen (1330), Osthoben (1346), Osthoffen (1438), and finally Osthofen.

The town lies near the left bank of the Rhine River (a couple of miles west of the river), just north of the city of Worms and south of Mainz.

Throughout the Middle Ages, many religious orders owned estates in the town (the Bishops of Metz, Mainz, and Worms; the monasteries at Hornbach, Mühlheim, and Lorsch; and the Hospitaller Knights). The village sheriff (or administrator), who also had responsibility for the neighboring town of Westhofen, was a vassal of the emperor and or various nobility.

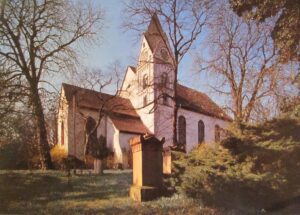

By 1195, a well-fortified town had been built on the hill (on the south edge of the current town), which is currently the site of the Bergkirche (literally, the “mountain church”) and the cemetery. This town was completely destroyed in 1241 by the troops of Bishop Landolf of Worms (possibly because the citizens of Osthofen were preying upon their less-well-protected neighbors by robbing them then retreating to the protection of the town walls).

Strife in the area continued until 1342 when Count Friedrich II of Leiningen became the patron of the village. From 1468 to 1798, Osthofen belonged the Electoral Palatine (often called the Palatinate or Pfalz region), ruled by the Elector Count Palatine. (Being an Elector meant he was one of the group entitled to elect the Holy Roman Emperor.)

As a result of the Peasants’ Rebellion in 1525 (which had its roots in the philosophies of the Reformation), the town of Osthofen was attacked by the Holy Roman Emperor’s forces. In 1548, Count Friedrich II recognized the Lutheran religion as an official religion in the Palatinate in addition to Catholicism. In 1560, the entire Palatinate area, under Elector Count Friedrich III, adopted the Calvinist Reform faith. The counts Palatine became chief drivers of the Protestant cause, with Count Friedrich IV becoming the head of a Protestant military alliance, known as the Protestant Union, in 1608.

The 1600s were a particularly turbulent time in the Palatinate (including the area around Osthofen), due to a series of wars (a result of religious differences and battles over succession of various nobility) and the plague. The area of Osthofen was right in the path of numerous armies, causing the inhabitants to flee the village several times during the 17th century. With the Elector Count Palatine being one of the key powers supporting Protestantism, this area became one of the primary battlegrounds.

The Thirty Years War (1618 to 1648) resulted in widespread battles throughout Europe, but primarily in Germany and the lands of the Holy Roman Empire. In 1621, the entire village of Osthofen was destroyed by General Spinola of Spain and his army. In 1637, the Osthofen villagers fled to escape the imperial army. Some hid in the ruins of the village until 1642, but from 1642 to 1648, the village of Osthofen was completely deserted. (Another source says the village was deserted as early as 1632.) Although the villagers began to return after 1648 when peace was declared, many had died—either as casualties of the war or from the plague which was sweeping through Germany. Less than 15 percent of the original villagers returned.

More war swept through the area between 1674 and 1676, as the French armies tried to annex this area to France. Then in 1685, the Count of the Palatinate died without an heir. King Louis XIV of France was determined to put his sister-in-law on the throne, who had a claim through marriage. (This became a power struggle between the Hapsburg and Bourbon dynasties.) The War for the Pfälzisch Succession (also called the War of the League of Augsburg) raged from 1689 to 1698, and once again, the town of Osthofen was deserted since it lay in the path of the warring armies. (This war also caused a large number of Germans from the Palatinate area to immigrate to America, primarily Pennsylvania, at this time.)

When the war was over, a few families returned. A 1698 census shows only 39 families (about 200 people) living in Osthofen—primarily of the Reform faith. (Six families were Catholic and four were Lutheran.) The town began to rebuild itself and grow once again. By 1710, the town was prosperous enough to pave its main street through town. With peace in the area, there were opportunities for new people to move in and help the area grow again. By 1722, the population had risen to 787 people.

It was sometime during this time period that Michael Schott arrived. The first documentation is of his marriage in 1717, at the age of 24, to Gertraudt Bitter. (Although, presumably he would have lived there at least a couple of years to be considered an acceptable husband to Gertraudt’s parents.) Michael’s father (also named Michael) died when he was just 12, leaving him living with his stepmother. This may have been one of the reasons he left his home village of Ober Gleen, Hessen, to migrate to Osthofen.

After the Thirty Years War and as the town grew, Osthofen contained a mixture of religions. Although the townspeople was primarily of the Calvinist Reform faith, there were also Lutherans (including the Schott family), Catholics, some Mennonites from Switzerland, and some Jews.

The Catholics used a chapel in the town for their services. The Lutheran and Reform congregations probably shared the Bergkirche (which had been built before the Thirty Years War on the hill where the fortified town had once been) until 1705, the year of the Pfälzisch Church division. The larger Reform congregation continued to use the Bergkirche, while the Lutheran congregation met on the site of the destroyed city hall (presumably making some repairs first).

In 1727, the town decided that they wanted to further repair and refurbish the city hall and use it once again, however the Lutherans refused to give up their church. By 1738, the situation had been decided in the Lutherans’ favor, and the city built a new city hall on another site.

In the meantime, the Lutherans were building a new church building. Opponents of the Lutherans harassed them during the construction, pulling down the church bell, striking the walls, and stealing a column that was originally meant to be used in the church for use in the new city hall. The Lutherans persevered however, and finally had a “proper” church in 1739. (In 1822, the Reform and Lutheran churches merged, becoming the German Evangelisch Church. Although the Lutheran church building still stands, it is no longer used as a church because the Evangelisch congregation uses the Bergkirche.)

The Lutheran congregation shared a pastor with Westhofen. Until 1720, the pastor’s home and main church was in Westhofen. In 1720, he moved his primary home to Osthofen.

Each of the churches also had their own schools. The Lutheran school existed from 1702 to 1822, and is probably where the Schott children attended school. It was about half the size of the Reform school (87 students in 1813 versus 214 students in the Reform school), and paid correspondingly poorer wages. The Lutheran school teacher earned 13 “Malter” of grain per year. A “Malt” was a unit of measure that could vary from 11 to 240 liters, so it’s difficult to know how well-paid the schoolteacher was.

The teacher from 1739 to 1772 was Konrad Helfenbeiner. His son, Johann Peter Helfenbeiner, succeeded him as teacher from 1772 to 1794. His daughter, Johanna, married into the Schott family.

By the 1780s, Osthofen had successfully risen from the ashes of the traumatic 17th century. The population in 1787 was 1727 inhabitants—an eight-fold increase from 1698. The town had three churches and three schools.

The area around Osthofen was a rich, agricultural area. In particular, growing grapes for wine was a very important crop. However, crafts and industries also played an equally important role in Osthofen’s development and prosperity.

A list from 1786 shows the following craftsmen: 2 barbers, 3 bakers, 3 beer brewers, 2 lathe turners, 3 shopkeepers, 11 coopers (some of whom also made beer and distilled brandy), 7 linen weavers (which would have included a couple of the Schott families), 4 stonemasons, 4 butchers, 9 millers (Osthofen had several mills), 2 sackmakers, 1 saddler, 4 innkeepers (although the translation of Schildwirth as innkeeper is uncertain), 1 locksmith/mechanic, 3 blacksmiths, 8 tailors, 3 cabinet makers, 16 shoemakers, 2 wagon builders, 2 master carpenters, and one village brick/tile factory.

The guilds were very important in 18th century Germany as a craftsman had to belong to a guild to sell their products. Presumably, the Schotts must have belonged to the linen weavers’ guild.

The guilds were very important in 18th century Germany as a craftsman had to belong to a guild to sell their products. Presumably, the Schotts must have belonged to the linen weavers’ guild.

The main guild hall for Osthofen’s craftsmen was initially in Alzey, then later in Westhofen. An example of their power: in Osthofen in 1744, the shopkeepers’ guild managed to make it illegal for itinerant peddlers and door-to-door salesmen to sell goods. In 1786, the “protected Jew” Hertz was forbidden to sell spices, oil, and vinegar because this was reserved for the guilds. (I’m not sure what the “protected” designation meant.) However, with the occupation of the area by France in 1798, the guild system came to an end.

Osthofen also had a number of village officials. Some of the positions that existed (certainly during the 1600s and many probably carried over to the 1700s) were: Bürgermeister or mayor, night watchman, police guard (who had the responsibility to ensure that no one drank wine during “forbidden times”), tax collector, town gate watchmen, a bell ringer (who had the responsibility of ringing the bell every morning at 6:00 a.m.), a building contractor for village buildings, firefighters, “vintner hunters” (who probably had the responsibility to watch over the vineyards in the fall), and wine coopers.

In 1792, the French army invaded the German areas on the left bank of the Rhine. They arrived in Osthofen in October. In the spring of 1793, the Prussian army came through and 1,220 Prussian troops were quartered there, which almost doubled the size of the town. After 1793, the French once again occupied the area. They quartered 1,670 men in the town in 1794, and plundered and confiscated supplies, including bread, wine, brandy, hay, straw, and chickens. In 1795, Osthofen citizens were recruited to man entrenchments near Mainz. Finally in 1797, the Prussian army made its final retreat, destroying the vineyards of Osthofen as they passed. In 1798, Osthofen, along with the rest of the German villages on the left bank of the Rhine, became part of the French jurisdiction called the Departement Mont-Tonnerre in Canton Bechtheim.

The French continued to quarter troops in the area. In 1806, Osthofen was asked to provide supplies for Prussian prisoners being held in the town of Alzey. The mayor replied that it was unreasonable to expect Osthofen to not only to provide daily support for the troops in the area, but also to provide more supplies when the town was already empty and some of the impoverished men and families were “already in misery.” He also makes the point that because Osthofen was near a crossing point on the Rhine, that more goods were requisitioned from their town than from other towns in the district.

The French occupation of Osthofen continued until 1816, but by that time, the Schott family had immigrated to Russia.

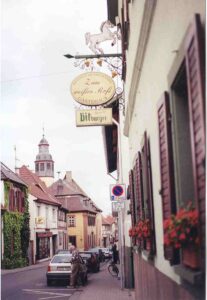

Today Osthofen is a small, pleasant town of about 8,000 residents that is an easy commute by train to Worms. Osthofen is known for its excellent wines, and each September celebrates the Wonnegau Region Winegrowers’ Fest.

Sources:

1200 Jahre Osthofen, Auf den Spuren der Vergangenheit. Druckhaus Seibert GmbH. Osthofen, 1984. [A valuable resource on Osthofen information with lots of historical details, photos, and maps – but difficult since it’s all in German!]

Blanning, T.C.W. The French Revolution in Germany. Oxford University Press. New York. 1983. [Scholarly to the point of being difficult to read – but has great information on a bit of history that seems to be invisible elsewhere – and that obviously had a direct impact on why the Schott family decided to leave Germany and go to Russia.]

Brilmayer, Karl Johann. Rheinhessen in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart. Verlag Weidlich, Würzburg, 1985. Reprinted from 1905 edition, Verlag von Emil Roth. [Some interesting stuff on Osthofen, but that old Gothic print makes it a last choice as an information resource.]

Kitchen, Martin. Cambridge Illustrated History – Germany. Cambridge University Press, 1996. [I don’t think the Germans’ migration to Russia is mentioned even once – but aside from that glaring hole, this is a good overview of the history of Germany.]

Wow…lots of history and interesting how we were part of it! Love it…thanks, Carolyn

Thank you for writing this. My ancestor too was from Osthofen. Isaac Mayer, successful businessman and Jew of Augusta, Georgia. He was also quite the importer of Rhine Wines from the fatherland, as I have found quite a few of his ads in the local newspapers. A brief synopsis of his life and ancestry on my blog: http://kindredheritage.com/paternal/mayer/

Not sure what source data and records you might have, but would love to take a look to see if my ancestors are there.

@Ryan – I have a book on Osthofen, though I mostly used church records to piece together my family history. Let me take a look and see what I can find about your family.

@Ryan – can you email me at carolyn@carolynschott.com? I’ve got a few pages from the Osthofen book that I can send you that might be interesting. No huge revelations, but still, some good tidbits of info where your family is listed.

Thank you for writing this. My family was from Ostehofen. My great grandparents were Heilfenbein

I have been trying to find things about my family for years.

Terri – be sure to read my other blog entry on Osthofen: https://carolynschott.com/ancestral_towns/welcome-back-to-osthofen/

Also – I have a Helfenbein connection! The brother of my 4x great grandfather, Philipp Jakob Schott b. 1740, was married to a Johanna Helfenbein.

muito interessante ler a história da cidade de meu bisavo, que nasceu em Osthhofen em1850 e imigrou para o Brasil em 1856 seu nome era Francisco Schmidt, muito prazer em participar das lembranças dessa querida cidade!

@Francisco – so glad you found this site! Maybe our ancestors were neighbors!

meu tataravo se chamava Jacob schmidt

Thank you Carolyn for all your research, and sharing it to. My family were also from Osthofen. I was wondering if you know anything about the brick factory. Apparently the men of my family worked their from the late 1600’s into the 1700’s. Johannes Jacob Fobel is my family. He was married to an Anna Elizabeth, but do not know her maiden name. I am at a dead end here. Any info would be greatly appreciated.

Thank you for taking the time if you have extra time to look into this for me.

Susan

@Susan – I suppose you’ve been looking in the church records for Osthofen? That’s where I found most of my info. Assuming your family was Protestant, you DO have to be careful though to check both the Lutheran and the Reformed records. When I first looked, I was looking in the Reform records and couldn’t find my family because they were in the Lutheran records.

Unfortunately, i don’t know anything about the brick factory. I did glance through the book on Osthofen history that I have, but nothing jumped out at me. (Of course, it’s a 500+ page book all in German, so I could have missed something.)

Sorry I’m not more help!

Hello

Any connection to FOHR?

Regards

Kate

@Kate – No, sorry. Were your Fohr ancestors from Osthofen?

…